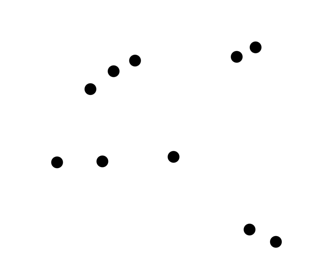

A swirling mass of dots on paper – so much more in the mind. Is it a kite you see? A diamond? Perhaps, a manta ray? Upon encountering abstractness our mind looks for shapes in smoke, constellations in stars, and then graduates on to constructing narratives from the events.

Such a tendency to build narratives help us spin sense out of the whirling chaos that the universe – like life – is. And this makes narratives a powerful tool for getting the general audience to engage with science.

With traditional scientific communication failing to breach the barrier to lay public, sci-comm scholars have touted narratives to be a potential answer.

Strength of narratives

Let’s take an example. Back in the rose-glint of childhood years, names like Chelonia mydas, Amphiprion ocellaris and Cnidaria, were flotsam in the streams of short-term memory that drained away. But when Nemo had to be found, the likes of sea turtles (Chelonia mydas), clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris), sea anemone (Cnidaria) and even the East Australian Current found the coveted storage space in our long-term memory.

Once again narratives stitch disparate thought-dots together, easing the train of thought into the state of comprehension. The sensory and emotional stimulation narratives provide, engage different parts of the brain, making the same information more memorable. Moreover, persuasive narratives manage to pull at our heart-strings and make us care.

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring tells a complex tale, a chronicle of the many-thronged harms of DDT to creatures as unalike as bees and vultures. And yet, the strong flames of emotions kindled in the readers ignited the modern environmental movement, and spurred the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the US. What a tale.

The creatures used to thinking of themselves as the “man-kind” and harbingers of “human-ity” finally began to passionately care for the tiny fish in the Pacific. And not just cared, acted. It highlights the ability of narratives to package varied phenomena into human scales, allowing readers to comprehend and engage with distant scientific topics.

Likewise, Randy Olson, author of Houston we have a narrative, blames “narrative deficiency” to be the hurdle blocking the flow of scientific communication to the general public. Thus, a logic-only sermon does not help anyone.

Narrative paradox

But do narratives always do the greater good? Or do we need to practice the word of caution as well? Dahlstorm and Scheufele raise this paradox as to how can science preserve its credibility as curator of knowledge while engaging audiences with a communication format that is agnostic to truth?

Revisiting our beloved Nemo’s story, it informed the public about the wondrous marine world, but also struck a death knell for clownfish. The grand saga of saving a fish from a fish tank, turned the funny little orange fish into a coveted pet. Our attachment to characters in the narrative came out as a double-edged sword for science, that in future needs to be dealt with carefully.

A perilous power then, narratives hold, remains mistrusted by scientists. Perhaps part of the reason is the association of “stories” with “fiction”. But a bigger reason is the lack of accountability and accuracy that abounds in examples of such writing. Unlike their cousins in peer-reviewed journals, narratives for the general audience seldom go through multi-layered grilling and fact-checking.

Complex scientific concepts, or critical findings, can be conveyed through narratives that can blur the line between reality and fiction. Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland is said to be a mathematical satire. Who can tell? Star Trek can boldly go where science hasn’t. But can the typical person tell the science from the fiction?

Precarious perceptions

Narratives are a powerful tool for shaping public perception. If I connect the dots for you, you begin to see the shape I see. In this case, as an eagle: the Aquila constellation. My way of connecting dots intrudes upon your own, to an extent that now, you can barely see a shape other than the one I intend you to see. It is the same way with stories and narratives.

When does the information and explanation become persuasion, and when manipulation? Science is meant to make people think. To look at data and evidence, and reach logical conclusions – ideally many possible conclusions. But if the writer does the thinking for the reader, they also need to stretch the ethical muscles.

The motives behind using narratives need deep consideration. Is one informing readers, leaving them capable to form their conclusions, or pushing them into seeing things a certain way? If a persuasive element is inherent in narrative communication, then should scientists stay away from using this technique for explaining their own research?

As Carl Sagan suggested in The Fine Art of Baloney Detection, “try not to get overly attached to a hypothesis just because it’s yours”.

What will it be?

Science cannot do without scientific detachment, but the science communicator can. Emotions are as much a part of narratives, as characters and plots. Should we then do away with narratives in science? Consider the two pictures.

Image source : IPCC

Image source: Pixabay

Image source: Pixabay

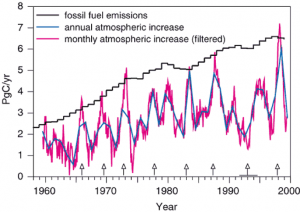

Which, in your mind and heart, is a stronger call for climate action? A number-speckled-spiky line? Or the picture that tells a story. Of a creature of snow stranded in a world creeping towards melting mayhem?

On a planet taken over by the overflowing story-fulness of the internet and media, narratives have become the dominant way the non-academia gets news and information. And science is in a crisis of trust.

From denial of climate change to fear of life-saving vaccines, the lay person needs to be reached differently. Narratives could be one way of building a bridge with the masses. Compared to traditional scientific writing, stories are adept at catching and keeping a reader’s attention – making possible engagement, retention, and persuasion. This is simultaneously a benefit and a challenge.

It is a web-thin line the science communicator must tread. It demands balancing the trust of the scientist and the interest of the reader while keeping the bridge intact. We must think carefully about what stories to tell, and where, and why? Additionally, the platform and the topic must decide how to build the narrative.

When the words “once upon a time” come together with science, it is treacherous territory. A lacuna between science and art. A web mixing scientists with not-scientists. It is here the science narrator reigns. And as another spider-creature’s story says, “with great power comes great responsibility”.