While clicking pictures using a DSLR or a smartphone, what is the one thing we try? We focus on the subject in the photo, be it our sweet grandma, a beautiful flower on the sidewalk, or anything else. We also block other unwanted parts of the scene and capture a memory to cherish.

Now, fast forward this fact to science communication, and engagement. Random, generalized messages serving the purpose of the deficit model do not help anyone. But if we frame the message, create a context, and block unwanted parts, science can be marketed better and help forge better public relations.

Nisbet and Scheufele highlight such importance of frames and other concepts that can help one shine their science communication in a special invited paper. Let’s get candid with it.

Taking the blame off science illiteracy

The beginning of the discussions rightly points out that when science and society see each other at crossroads, blame shifts on science illiteracy among the public. The scientists (or the communicators) do not think that their methods and efforts might also be part of the problem.

Just think, how would you feel if your teacher kept blaming you for not excelling in grades. While at the same time, their methods of teaching do not justify your academic potential and capabilities? Surprise surprise, a meta-analysis from 2008 also points out that science illiteracy accounts for a small variance in how the lay public forms opinions about science.

Rather factors such as ideologies, religious belief, and partisanship exert stronger influences. So, applying traditional approaches to engage the wider public, which depends on cognitive shortcuts and heuristics to make decisions, won’t work.

While the public respects science, trusts scientists, they deviate from science when it conflicts with values they deeply care about. But, even those are not the cases to lose hope. Understanding how to initiate dialogue, invite various perspectives, facilitate participation, learn from disagreement, reach consensus, and avoid communication mistakes, can help navigate the landscape.

Criteria of judgment, layman apply.

The researchers laid out the following criteria the lay public applies to reach judgments about science:

- Does scientific knowledge work? Do public predictions by scientists fail or prove to be true?

- Do scientists pay attention to other available knowledge when making claims?

- Are scientists open to criticism? Are they willing to admit errors and oversights?

- What are the social and institutional affiliations of scientists?

- Do they have a historical track record of trustworthiness?

- Do they have perceived conflicts of interest relative to their associations with industry, government, universities, or advocacy groups?

- What other issues overlap or connect to a public’s immediate perception of the scientific issue?

- Specific to risks, have potential long-term and irreversible consequences of science been seriously evaluated, and by whom?

- Do regulatory authorities have sufficient powers to effectively regulate organizations and companies who wish to develop the science?

- Who will be held responsible in cases of unforeseen harm?

Of course, a single person may not come up with all these questions. But different questions can come from different sects of the public. As seen in a great example mentioned by authors.

Frames and science communication

What are the frames? Per the definition, “ frames ” are interpretative storylines that communicate what is at stake in a societal debate and why the issue matters. To understand, frames serve as storylines that set the stage for a societal debate and the issue at hand. Let’s understand this with the climate change issue as an example.

In the 1990s, Frank Luntz, an American political and communications consultant, framed climate change warnings as scientific uncertainty and an unfair economic burden to the US. Al Gore and the scientists who worked on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) were accused of alarmism.

The warnings about arctic regions and animals that were remote and away from the public’s visualization also made things difficult. But by the end of 2007, the advocates of climate change set the frame in favor of economic development.

Framing climate change as adverse for public health, as an economic opportunity for creating green jobs, and climate stewardship as a religious moral and ethical responsibility helped the cause.

It highlights how framing the issue and science successfully can help create a link between two concepts and make the audience feel connected. But another side of the coin demands considering the personal experiences, conventional wisdom, or culture the public comes from.

Hence, while framing the message, it’s important to remember that we are only setting up a constructive basis or context for the conversation to happen and not selling the public on it. Setting frames in local contexts also brings in the local media coverage to spread awareness in a targeted manner.

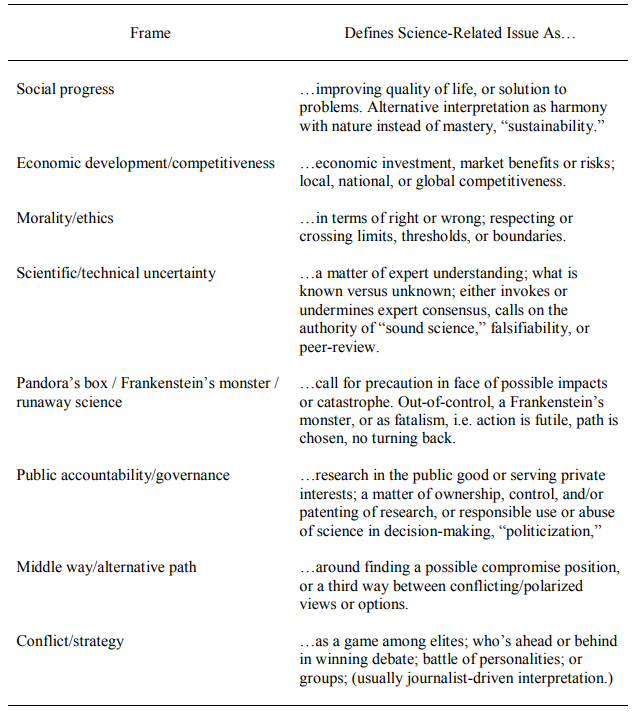

Typology of frames in Science Communication

Accordingly, Nisbet proposed a typology of frames that can be used for science-related policy debates (and, in our view, can help general scicomm as well).

The article further illustrates notable examples from themes of evolution, nanotechnology, and plant biotechnology.

Future directions for SciComm PR

Culminating the paper, the authors put forth commendable recommendations:

- Offering courses and training in communication to college and doctoral students will become the scientists who will have to give interviews, interact with the public at some point, and communicate with policymakers.

- Encourage public involvement and dialogue, initiate early discussions for controversial sciences, and spent resources on sampling, recruitment, and turnout.

- Utilizing data from surveys and other systematic research to understand audiences and communicate effectively.

- Prioritizing and focusing on public values to add personal relevance to communication.

- Going beyond the elite set of audience who have prompt and easy access to information and using local media, scientists, institutions, and organizations to reach maximum audiences.

- Address information gaps at local levels by promoting local television and radios for dispersal of science information.

- Promoting science literacy by focusing on a curriculum for civic science media, teaching teachers and students about quality online sources, constructive use of social media, and more.

- Identifying, recruiting, and exploiting opinion leaders’ credibility to reach a greater audience in a more trusted manner.

The latest STIP Policy Draft 2020 by the Government of India, also talks about the important issues of Capacity building, Research, Outreach, and Mainstreaming Science Communication. Download and read the document.