‘Words are, in my not-so-humble opinion are our inexhaustible source of magic, capable of both inflicting injury and remedying it.’, lines by Dumbledore to Harry. As science communicators, words are magical tools that can help us compose effective key messages for audiences.

But a wrong spell can leave audiences baffled and clueless. Especially in the present age when the public has access to new information environments where they choose what to see and how much attention to pay.

Such choices also come under the influence of information sources that choose what and how to present. So, smaller attention spans, the need to present useful information effectively, and channel it across relevant platforms require us to draft messages carefully.

Let’s learn this by utilizing two powerful examples from two powerful nations in the world.

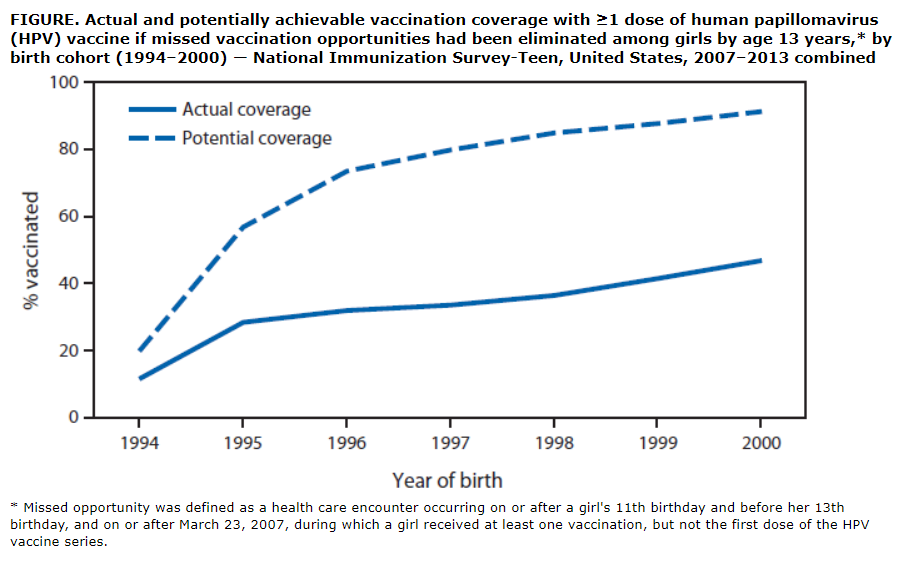

Tale of HPV vaccine from the USA

In the USA, HPV infects 79 million Americans and claims the lives of 3,000 women annually due to cervical cancer. So, Merck & Co. marketed Gardasil, a vaccine protecting against most strains of HPV. Gardasil underwent fast-track approval by the Food and Drugs Administration (FDA). But, the vaccine was not met with acceptance rather a great upheaval. A series of actions and decisions made by the manufacturers of vaccines triggered a science communication controversy that plagues the HPV vaccination rate.

Cultural Issues

Due to fast-track approval, the vaccination got a female-only approval. It was because only women faced serious enough risk from HPV, a causative agent of cervical cancer. But here, cultural cognition came into play. The vaccination drive demanded adolescent girls’ parents to vaccinate them against a sexually transmitted disease for school enrollment.

Of course, it did not go down well, and out came the headlines such as “Defusing the War over the ‘Promiscuity’ Vaccine” in Time Magazine, “Catholic Schools Debating Moral Issue of HPV Shot” in The Toronto Star, “Slut Shot” in Voice Columns and many more such depictions. The shot became a mark of a loose sexual character, shaming the girls and offending the culturally liberal groups.

Legislative issues

Another point of blunder was possibly Merck’s legislative campaign to seek the rapid approval of school mandates for the vaccine. Merck paid for the lobbying efforts of an interest group, Women in Government, dedicated to women’s health. Women in the Government advocated sexual education in school and opposed restrictions on abortion.

What appeared as a sensible decision backfired, provoking the religious conservatives. Merck then made contributions to a governor who held important stature in US religious rights. However, this came out in media, forcing Merck to cancel the legislative drives for Gardasil.

Lesson

If the company had not sought fast-tracked approval, then the vaccine would have been approved for both boys and girls in three years. The vaccine would then have found a place in school mandates, just like the HBV vaccine. The issue highlights the role of cultural cognition in science communication.

Further, instead of a legislative campaign, the vaccine would have benefitted from a proposal to seek approval from the CDC to add the vaccine to the list of immunizations necessary for school enrollment. The public health boards, insulated from the politics and interest groups, would have made the decision.

Thus, the incident shows the need to consider the interplay between science and culture.

UK Government’s COVID-19 messaging

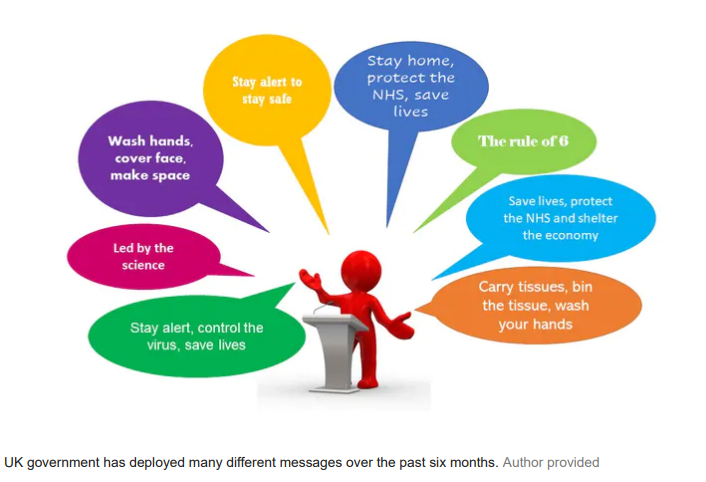

COVID-19, a pandemic of the 21st century, landed in the UK in late January 2020 and continues to trouble the nation. Like all the nations around the world, the country began its health awareness campaign in March 2020. As noted by Sally Dibb, many gaping errors characterized the UK health awareness campaign, a marketing and society professor at Coventry University, in her article for the Conversation.

When the public needs clear and consistent messages, the health campaign’s language appeared complex, confusing, and kept changing. As per Sally, the government misses out on the first rule of keeping things simple. Consider the phrase, “not meet in groups larger than six,” followed by “with some limited exceptions.” What are the exceptions? Where to find these exceptions?

In May, the administration changed the message from “Stay alert, control the virus, save lives” to “Stay at home, protect the NHS, save lives.” It again confuses the people, and many communication experts pointed out the unnecessary change when the situation continued to be the same. Other examples of lack of consistency are:

A report by C-19 National Foresight Group, a group set up to support UK COVID-19 response, mentions, the general tone, style, and timing of the government’s messages was the cause of widespread irritation among local leaders, who were concerned at its negative impact on public trust and who blamed it in part for the failure to develop a joined-up local and national response to the pandemic.

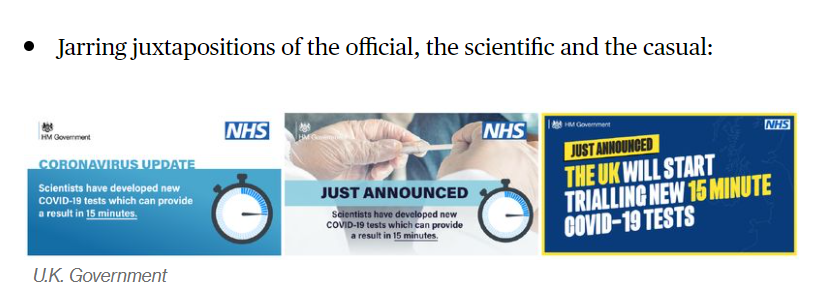

An article by Bloomberg detailed the erratic styles of posters, lack of clarity, and design. For example:

The campaign lacked a central theme upon which the layers of messages could be built as per changing situations. Such messaging eroded people’s trust, created confusion and paved the way for the loss of lives.

How to design effective key messages?

The above two examples emphasize the need to carefully craft the messages and deliver them to the public most simply and effectively. Often simple things are not done easily. Here we bring you a checklist that can help you craft key scientific messages.

- Utilize the goals and objectives of the communication campaign as your guiding light in designing the messages

- Research your audience, know about their cultural cognition, preferences, knowledge levels, etc.

- Determine the communication needs of different segments of audiences, for example, per the language, technology literacy, and other factors

- Prepare a master narrative that will help you stick to the central theme and essence of the message.

- Prioritize the information and reduce it into short form

- Always keep the messages concise, consistent, accurate, and simple to follow. You can follow the 3Ms of science communication.

- Please pay attention to the words you use. You can maintain a vocabulary beforehand and stick around it.

- Always maintain an active voice.