Science has a marketing problem. By this we mean it fails to reach masses whether a layman, school student, policymakers, and more. It’s not only us who are saying it, but the renowned says this too. In 2007, Larry Page, Google’s co-founder while delivering a plenary lecture at the American Association for the Advancement of Science conference said, “If all the growth in the world is due to science and technology and no one pays attention to you, then you have a serious marketing problem.”

Everything is science, from basic life functions of breathing, eating, walking to advance things such as gene editing. Yet, scientists remain reclusive, people see science as out of their scope, and science does not make the impact it can. What are the areas of the problem? What are we as a scientific community missing out on? Apparently, we miss out on a lot, much of what we ignore consciously.

Expecting a lot from scientists

Ask a scientist about their daily schedule, and they will lead you through the intricate tasks of experimentation, meetings, academic goals, manuscript writing, and much more. Moreover, the current system does not train scientists in the art of communication, behavior, outreach, and engagement.

Thus, only expecting the scientist to juggle their research duties with composing popular science pieces, understanding and engaging with the public raises problems. They are humans with personal life, and we cannot expect everyone to have the same desires.

Thus, supporting the scientists with a team of creatives and experts who can help them navigate the communication landscape proves crucial. Without this, science will continue to have a marketing/PR problem, failing to reach the folks.

Is there a lack of open dialogue?

Talking about the Indian scenario, much has been done in terms of science communication. The premier Indian institution’s reserve positions for outreach officers are events, festivals, congress, budgeting for science popularization programs, and increasingly wider scientific issues coverage. Still, we suffer from drawbacks where either we feed information to the public or do not do that at all.

Vasudevan Mukunth, a science editor, while working with The Hindu, in 2013, called out to Indian readers to write in with what they thought of science communication in India. The responses were as follows:

- Low degree of coverage about science news

- Stories in the press not very relatable

- Different stories are simplified to a different extent.

- Many people want to know the science behind new gadgets rather than the gadget themselves.

Upon extracting more such insights, one can call for more openness of dialogue from the scientific community. The ivory towers where scientific knowledge arises need to lower their guards and engage with the public.

Are we listening to the audience?

Every one of us orders from Amazon, Flipkart, and even other small businesses we love. What do all these have in common? They listen to you, what you like, what you want, and do their best to stock up on most love up stuff.

And they do this by staying in touch with you and your behavior. Similarly, in science communication, we need to shed our assumptions about what people need to know, do know, and what to do as a result.

In line with this, Vasudevan’s call found another interesting response stating Science is simply a way of looking at the world – keep this in mind when you write. Thus, if a communicator or scientist keeps themselves guarded away from their audiences, they are essentially pushing themselves into a PR nightmare.

Need to help people make informed decisions

Raghavendra Gadagkar, Professor, Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science, in a panel discussion held in Vigyan Bhavan, highlighted, ‘If we want everyone to make evidence-based decisions, we must make it possible for everyone to have access to and be able to understand the evidence.’

As scientists and communicators, we are here to help people understand the evidence and develop a scientific temper. However, the monotonous and sophisticated science monologues delivered to audiences repel them and create a gap filled with pseudoscience.

Research has even pointed out the discontent between scientists and journalists.

Results show that scientists claim that journalists ignore local scientists, tamper with their research findings, and do not consider science an interesting beat to cover. On the other hand, journalists claim that scientists do not want to share their work, and they do not explain science in simple terms.

Are we aware of segmenting the audience?

Marketing 101 and even the basics of PR always demand one to segment their audience. What segmenting the audience entails? Segmenting involves identifying the group of people who are meaningful as per the context of your communication goal.

You cannot impose your communication goal on everyone, but you can make the relevant group of people actually care. One can segment the audience based on geography, demographics (age, gender, profession, etc.), psychology, and benefit. To segment the audience, asks yourself some basic questions:

- Who are my audiences, and what are their needs?

- What piece or strategy of communication will help meet the target group’s needs and wants?

- What strategies and resources can help me effectively connect with the group?

Here some knowledge of how businesses work, what marketing and PR strategies they follow can really help a communicator. No, we are not asking you to go to a business school. Just a search on Google will show up informative blogs written in simple language that can help you. Or let us know if you want us to create such resources.

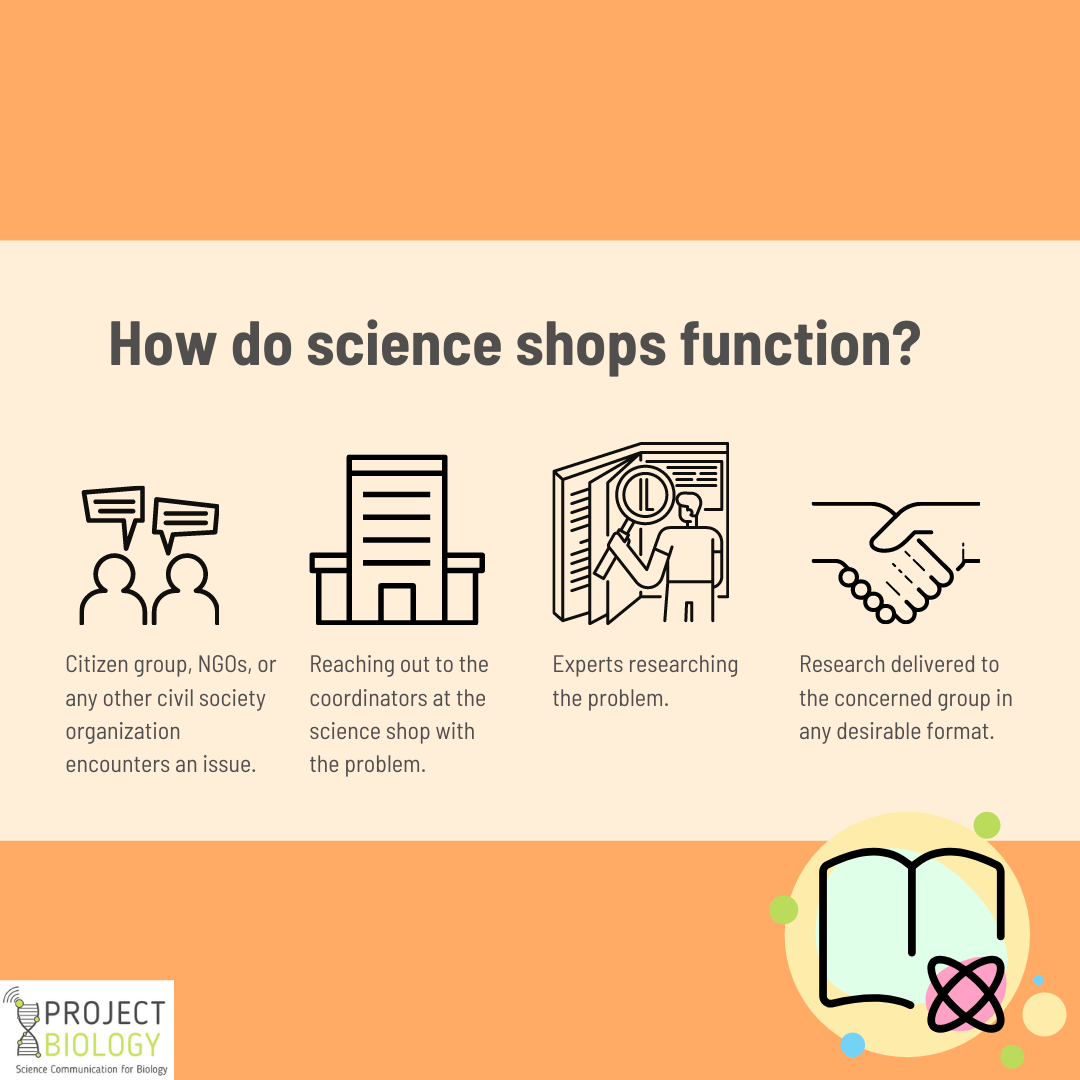

Are channels to learn from people open?

Communication becomes purposeful and effective when both the parties involved feel listened to and achieve a common goal in science-related issues that impact decisions ranging from policy to individual level. Thus, learning from the audience remains equally important as teaching them.

Currently, the information dissemination model dominates the communication scenario as highlighted by Nisbet in a report for Academy Health. While reviewing the dissemination and translation paradigm, the issues of perception gaps in media, the contest over frames, and others, the paper suggests alternative strategies.

These strategic changes include

- Investing in new frames of reference and cultural voices;

- Proactively widening the menu of policy options on the table;

- Protecting an issue from easy polarization; and

- Investing in localized public and media forums that provide context for health care problems and trends while bridging perspectives

Another research looking into scientists’ objectives for public engagement shows that scientists prioritized communication to defend science from misinformation and educate the public. While they least prioritized communication that seeks to build trust and establish resonance with the public.

Building trust and resonance does require scientists and communicators to listen to the public. If we do not listen to the public, we essentially shield science away and burn the bridges where science and society can meet and exchange ways.

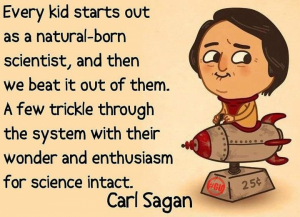

The Sagan effect

Let’s dive into this with a perspective shared by a scientist only. Anindita Bhadra, in her article, Have we scientists failed our society? Puts across the crude and unfortunate realities of academia. She writes,

‘Many consider research that can be communicated to the uninitiated, shared in the public media, discussed by non-scientists to be of inferior quality. When a piece of research gets highlighted by the public media, we should rejoice and congratulate the researchers instead of mocking them for not doing science that is of “high quality.”’

To this day, the scientific community holds its core academic beliefs and shies away from the spotlight. Those who venture out are labeled as not serious about the science itself, perfectly embodying the Sagan effect.

Carl Sagan, in 1991 popularized astronomical science and received a nomination for membership to the National Academy of Sciences. But the nomination failed. He also faced denial from Harvard for a tenure position.

His suffering came to be labeled as the Sagan effect. A perception that popular, visible scientists are worse academics than those who do not engage in public discourse.

However, later analysis of his work showed that he contributed fairly academically as much as his peers. To date, the perception that scientists who engage in outreach are less successful continues and do face the consequences. It could be one of the reasons that many scientists still evade the spotlight. And so science continues to have a marketing/PR problem.

If you too feel the science you do can be disseminated better, feel free to reach out to us for help.