Clinical trials, not many a layman knew this term before the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic iterated the indispensability of clinical trials in developing novel drugs, vaccines, improving medical interventions, and augmenting health care. It also highlighted the central role of clinical trials in ensuring the effective use of the scientific community’s acumen and taxpayers’ money. We even witnessed the heavy reliance of clinical trial registration on public engagement, with healthy volunteers and patients as research partners.

Yet another learning comes from the non-expert background of participants of a clinical trial. Likewise, employing the participants remains the biggest challenge. It demands the use of lucid language to help the participants understand the related nuances. So, how as communicators and researcher we can do that? How can we engage and involve participants with no scientific background?

Taking the learning from stories, anecdotes, and narratives given by Michael F. Dahlstrom in his article on “using narratives and storytelling to communicate science with non-expert audiences,” one can charter a path for themselves. The intrinsic benefits of storytelling in science include a spell out of complex ideas for the lay audiences, improved consumer trust in novel vaccines and technologies. In a nutshell, narrative communication helps create Simple, Unexpected, Concrete, Credible, Emotional, Science Storytelling (SUCCESS) of innovations and discoveries to benefit society.

So, today, I take you on an anecdotal journey, peeking into the process of demystifying science through stories.

Simplify medical jargon

Many years ago, I had the chance to work on a clinical study that involved terminal stage IIIc/IV ovarian cancer patients. Apart from performing molecular biology experiments in the research laboratory, I also involved myself in inpatient enlisting. It was a simple task: explain the trial’s goals, the medical procedure, the benefits of the clinical project to the patients, and enlist.

But on the very first day, I faced a major roadblock to recruiting. Both the patient and the caregiver I talked to were unconvinced and declined to participate. Taken aback by the complexity of a seemingly simple task, I talked to a medical resident. That’s when the learned and experienced resident made me realize that I had peppered the conversation with medical jargon. As a result, both the patient and caregiver went away.

Let me share with you an excerpt from my first unsuccessful attempt:

“ We will administer neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical resection of the tumor. Then we will use adjuvant chemotherapy for maintenance therapy.”

In the above sentence, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection, adjuvant chemotherapy, maintenance therapy are medical jargon. This intimidated the listener, and they refused to enlist.

Learning from the response

As I rued over my first unsuccessful attempt, I wondered how to communicate effectively? I then recalled Robert McKees’s wise words: “storytelling is the most powerful way to put ideas into the world.” And that is what I tried. Hence, post my roadblock and the learning share, I came up with the simplified story of the complex medical jargon:

“ There is a ball of cells in your body called tumor that looks like a big orange. We will first give medicine for 2-3 months to decrease the size of the orange. After that, we will perform surgery to remove the leftover pieces of orange from your body. And then give more medicines to try and stop the orange from appearing in your body again.”

This story, with its analogies, removed medical jargon from the conversation, explained the goal, simplified the medical procedure, and encouraged the listener to ask questions. Consequently, this narrative became my magic wand that motivated patients to seek more information and enlist.

Encourage patients and caregivers to ask questions.

We all hear that ignorance is bliss. But, ignorance about the clinical procedure’s outcome may lead to an unwillingness to participate in the clinical study. Moreover, working alongside healthcare professionals helped me appreciate that a large influx of patients often corners consultants to diagnose within a short time. During these clipped conversations, clarity and comprehension seem to be the melting pot that influences decisions to accept or reject medical interventions.

Let us take an example of a possible patient concern:

“What will you do if the orange ball returns after surgery and medication?”

In the above question, the patient and their caregivers look for an honest opinion to help them decide whether to accept the medical intervention.

Let us take an example of addressing the patient concern in simple words:

“In case the orange ball reappears there are many other medicines and interventions available for use. For example, if you get a fever we can use paracetamol that reduces fever. But, along with fever if a body ache arises then we will use Calpol.”

This story brought in a known symptom called fever and names of familiar medicines. Analogies reassure and allay fears of the unfamiliar. Thus, it is important to keep conversation simple yet informing and engaging.

Stories from the patients: Testimonials

Before we join a gym, buy the latest gadget, invest in shares of the company, we always look for user reviews. So, why should opting for a medical intervention be any different? A major fear about participating in clinical trials involves being misled to join a clinical study, promising ambitious study outcomes, and becoming “lab rats.” Thus, the best way to allay trepidation and enhance recruitment are testimonies from enrolled participants or those diagnosed with the same condition.

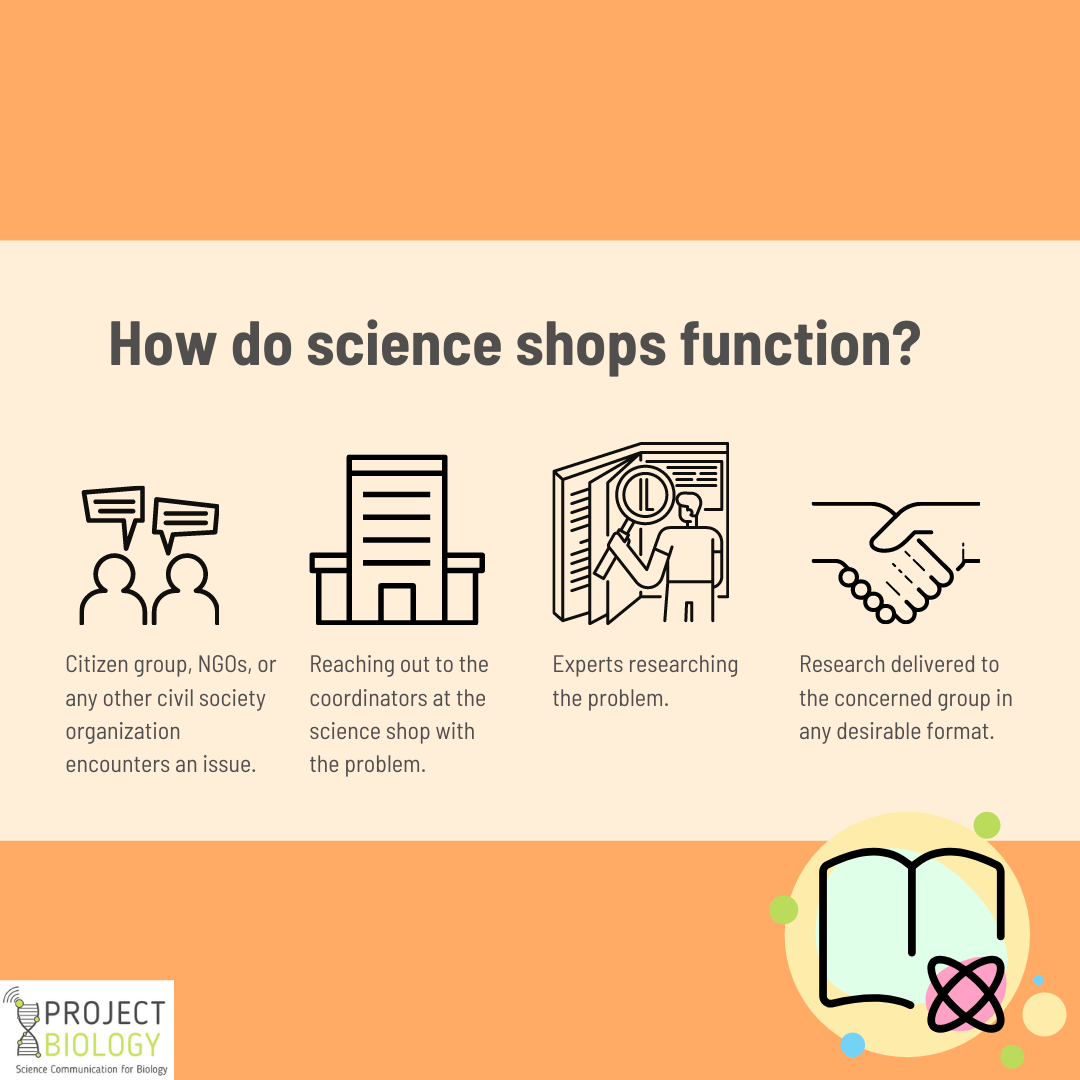

For example, in Canada, the Patient-Oriented Research units developed local Support for People and Patient-Oriented and Trials (SUPPORT) groups to bring stakeholders like trial participants, clinical research teams, and medical professionals same page. It helps enhance the design of clinical trials and research outcomes through public engagement.

Let us take an example of a testimonial from Patients Like Me:

“When diagnosed, I felt overwhelmed and alone in the world. I joined PatientsLikeMe and found thousands of others with my condition. I felt such a relief I was not alone.”

A newly diagnosed person is reassured that the person is not on one’s own. Testimonials stating the stories of ongoing and previous patients give strength, courage and put uncertainty to rest.

Patient advocacy through narrative communication

The unforgettable “Doctor’s trial,” which held Nazi doctors accountable for heinous human experiments, had laid the foundation of The Nurenberg Code in 1947 to protect future clinical trial participants.

Patient advocates communicate the medical concerns of participants to healthcare professionals to assure the health-related quality of life. Types of patient advocacy include layperson advocates, governmental agencies, patient representatives, and patient advocacy groups.

These patient representatives have multifaceted roles:

- liaison with participants,

- promote ethical research activities,

- communicate science to the society,

- collaborate with clinical trial sponsors,

- assist in the development of study protocols and informed consent forms,

- advocate good clinical practices and policies in favor of participants,

- speak with the media, practitioners, and the pharmaceutical industry.

Let us take an anecdote from North Shore Patient Advocates:

“When I heard your talk at the library a few months ago, I learned all kinds of questions I needed to ask to ensure that my rehab was covered after my knee replacement surgery was done. It’s all so overwhelming; thanks for making this information available to the general public! It gave me such peace of mind during my recent hospitalization!”

Anecdotes from patient advocates help build support and disseminate valuable information independent of borders.

Other forms of narrative communication

Outreach using narrative communication of science is possible through podcasts, short videos, street plays, and even comic strips, helping patient advocates communicate science.

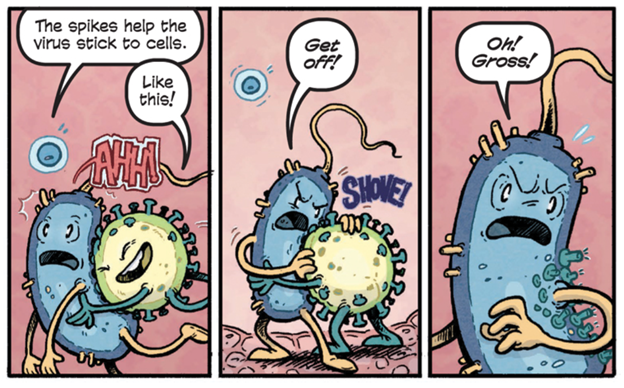

Let us take an example of explaining science through a comic strip:

The excerpt from the “Science Comics Plagues: The Microscopic Battlefield” by Falynn Koch explains how a virus is attached to a cell? Humorously, virus invasion in a human body is explained by visualizing a yellow color virus hugging an annoying blue color cell through its green spikes.

Narrative communication using science comics. (Image courtesy: Brigid Alverson)

Science is an orphan without communication.

Before 2020, a handful had heard of the Coronavirus. The pandemic brought unforeseen lockdowns and worldwide economic meltdowns. But, these events also brought together the layperson, pharmaceutical giants, and healthcare professionals. All and everyone asked the same questions about the origin of the disease, symptoms, precautions, and medical interventions.

Irrespective of the language, ethnicity, and nationality, everyone looked for the dos and don’ts of the disease. Communication on COVID-19 dominated every conversation through infographics, radio programs, and news. The pandemic reminded us of the importance of broadcasting scientific findings in simple forms to the public and the value of patient testimonials.

Let us take an excerpt from Ahmad Ayyad’s COVID-19 testimonial:

“Ayyad was on a ventilator at The Johns Hopkins Hospital for 25 days and lost more than 60 pounds during his ordeal. His doctors say his physical fitness, positive attitude, and the support of friends and family are helping him recover from the disease and the toll of long-term ventilation.”

Reading anecdotes like Ahmad Ayyad’s reinforces solidity, hope for those in similar situations and assists in an online presence of community outreach. In our ever-changing world with numerous challenges, discoveries become relevant when the non-expert audiences make science part of their daily conversations through storytelling that resonates and establishes cultural identities.

In 2018, the Public Communications of Science and Technology Network (PCST) conference gave impetus to narrative communication by combining science with storytelling to enhance public engagement. In the words of Sean Caroll, “science is not opposed to storytelling. Science is a genre of storytelling. Stories of the real world, inspired by observations thereof.”

I hold a Ph.D. in Vascular Developmental Biology, work experience in clinical trials management, a freelance writer and a nascent poet.