The increasing visibility of trans lives and the ongoing battles for trans rights have led to some positive changes in recent years. But many issues still prevail. Lack of sufficient support and empathy from the healthcare system and the broader scientific community remains one example. We shall talk about it in this article and what healthcare providers and science communicators can do to combat it.

First of all, let’s talk about terminology. In this article, I shall use the term transfeminine to refer to people assigned male at birth but identifying as women or as any gender identity except their assigned one. The term transmasculine refers to people assigned female at birth but identifying as men or as any gender identity except their assigned one. My own perspective comes from the transfeminine side of the spectrum, which will affect how I discuss each of the issues below. But most of these points can apply to other trans people too.

Is the healthcare system trans-friendly?

After getting the terminology in place, the first issue to consider is how most healthcare providers refer to trans people. In our previous article about queer sensitivity, the issue of misgendering came to light. Additionally, it remains a disturbing truth that most trans people interacting with countless (not all) healthcare providers experience dehumanizing experiences.

Though an increasing number of healthcare providers show sensitivity and empathize with trans people, their numbers remain less. Even many of those who work in transgender health, and intend to support trans people through medical transitions, are often trapped in essentialist ideas.

These problems arise from a relatively narrow view of one’s expertise. Such views render the individual agency and identity of a trans patient to be inferior per the healthcare provider’s own judgments. Such judgments often refer to how well the patient did to be identified as one gender or another.

How can a healthcare provider communicate better?

Reducing the practitioner–patient power disparity and empowering patient advocacy can lead to effective communication and health outcomes.

One should refrain from imposing their opinions regarding the morality of a trans patient’s gender identity or the decisions related to their trans status.

Practitioners who refrain from this can communicate respect and empathy and explain that practitioners should separate their personal perspectives from their professional behaviors.

The simplest and correct approach is to ask someone for their name and pronouns in all such cases. Further, asking the terms, they would like to use for body parts or bodily functions for which gendered terms are usually used also helps.

Moreover, it can be a good practice to take this approach with all of one’s clients, and not only with some clients who ‘appear’ trans or gender non-conforming.

Also, while it is prudent to use they/them pronouns to refer to anyone whose pronouns you don’t know yet, once one clearly states their choice of pronouns, one can proceed with using those stated pronouns.

Avoid microaggressions

Besides misgendering and dehumanization, there are various micro-aggressions that one must be wary of and avoid. Examples include:

- outing someone without their explicit consent,

- asking someone about their medical transition if it is not directly and specifically related to the purpose of your interaction with them,

- assuming that their transition is the cause of any other unrelated health issue that they face (i.e., the trans broken arm syndrome),

- asking any questions about trans people in general, which you could have googled by yourself, or

- indeed saying anything that you wouldn’t usually say to a cis person.

Also, do remember that trans people are not educational opportunities. Thus, any conversation must stick to its purpose without turning it into a discussion on gender and trans issues if they don’t serve the primary purpose.

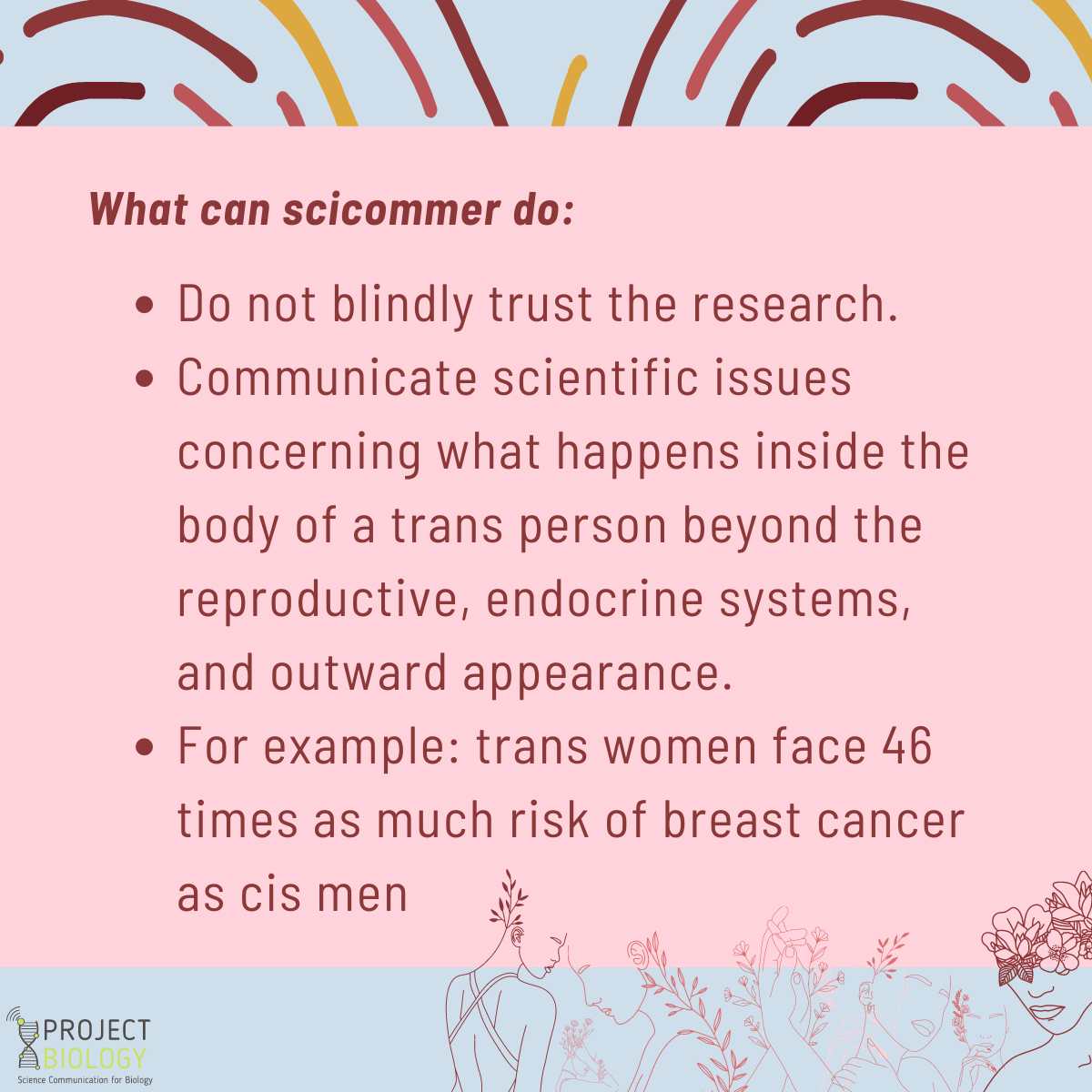

Forming fair and unbiased perceptions: do not blindly trust the research.

The next issue comprises empathetic healthcare providers or science communicators falling prey to transphobic ‘research’ (such as these examples). Such research often propagates dangerous and bigoted notions about trans people. Even the history of trans healthcare claiming to support trans people also comes littered with examples of gatekeeping and older norms or dangerous standards invalidating for many trans people.

Even today, in practice, if not on paper, the presence of gender dysphoria and the intent to medically transition are considered prerequisites for someone to identify as trans, which is wrong. As we said above, the simplest approach is to ask someone how they identify and respect that.

Moreover, the evolving standards and definitions as determined by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), American Psychiatric Association (APA), and the World Health Organization (WHO) are increasingly moving away from ‘gate-keeping’ to ‘informed consent.’ Thus, it becomes important for anyone working or communicating to stay updated on such developments in this field.

As for transphobic ‘research,’ such as the examples cited above, it is important to remember that most of these baseless theories and notions have already been severely criticized and refuted. Thus remaining ignorant of or ignoring the most up-to-date scientific understanding of trans issues does not bode well for science communicators. To avoid this consulting with sensitivity readers and the members of the community can help.

Thinking of issues in a holistic manner

Besides transition-related healthcare, there are other aspects of healthcare where the needs of trans people should be considered as well. For example, in the field of mental health, it should not just be about gender dysphoria but other mental health issues faced by trans people as well. These issues may be made worse by the stigma and discrimination faced due to their trans identity.

Mental health support is, after all, an ongoing need for everyone, not just those who may be ‘diagnosed’ with some condition or those seeking to transition medically. Next, when it comes to reproductive health, just as we discussed in another article, having the right information and access to the same choices as any cisgender person remains the right of every trans person. It shouldn’t be assumed as irrelevant for someone just because of their gender identity or sexual orientation.

Communicating the issues lacking in trans-affirming healthcare

Finally, we need to acknowledge that many questions about the long-term effects of various steps in medical transitions remain. Moreover, the research on many of these questions still lacks severely. Even today, much of the conversation about hormone replacement therapy (HRT) and other trans-affirming healthcare focus too much on one’s outward appearance and helping a trans person ‘pass’ as their identified gender.

It needs to focus more on what happens inside the body beyond the reproductive and endocrine system and one’s social appearance. Even where research does exist, many who work in this field remain unaware of it. For example, HRT for trans women is routinely limited to anti-androgens and estradiol and not progesterone, even though research indicates progesterone is as important for trans women’s long-term health as cis women.

In many cases, the long-term risks and outcomes are compared with the gender assigned at birth. Instead, such comparisons should find basis with cis people of the same gender. For example, one may see a report which states that trans women face 46 times as much risk of breast cancer as cis men. It exemplifies how transphobic writers may misuse information. However, if one compares this risk with cis women, it is not a concern. Thus, the fact remains that trans people deserve the same treatment and respect as cis people. Any research or communication efforts should be directed towards that purpose.